Today, we are happy to introduce guest contributions written by Roland Baker, Virginia Dinino with Livio Straka (All at the European Central Bank). The opinions expressed belong to the author and may not be shared with the author’s organization.

Criticisms of globalization and European integration are usually based on the trade-off between efficiency and social justice. According to this argument, globalization often violates Rawls’ principle of fairness because it raises the incomes of a few people while leaving part of society behind.

So far, the literature on the impact of globalization on inequality has focused on trade, an area where the distributional impact is relatively well understood (see Ebenstein et al. (2014) for advanced economies and Goldberg and Pavcnik (2007) for emerging economies). And developing economies). However, globalization is a multifaceted concept, and other aspects are also worthy of attention. Recent literature on the distributional effects of financial liberalization (Furceri and Loungani, 2015; Furceri, Loungani, and Ostry, 2019), while studying the impact of membership in “global clubs” restricts its focus to such organizations. The impact is on trade, but it is not trivial to establish (Rose, 2004; Rose, 2005; Subramanian and Wei, 2007).

In a recent paper (Beck et al., 2021), we re-examine the impact of globalization on income and inequality by identifying the exogenous changes of national globalization in the broad concept of globalization, including (i) Join the “globalization club” (ii) large-scale financial liberalization events and (iii) external tools to change trade openness. This allows us not only to solve the endogeneity problem to a large extent, but also to engage in policy debates about the membership of the organization considered in our first definition of globalization.

Our list of globalization clubs includes the WTO, the European Union, and the OECD, all of which require their members to pursue some form of free trade or investment policy, or both. In order to isolate the impact of financial opening shocks, we also study pure financial opening shocks based on the huge changes in popular measurement indicators. in Law Financial openness originally reported in Chin and Ito (2006). In another robustness test, we used a Bartik-type tool designed to capture “trade opening shocks” that are exogenous to individual countries. In this case, we will pre-determine international trade exposures. Interacting with global trade growth, this is an exogenous change in most cases. country.

In all norms, we take into account the past total factor productivity (TFP) growth, and the purpose is to separate trade integration from skill-biased technological change, otherwise it will be difficult to separate it from globalization (Acemoglu, 2002) .In addition, we control several political and economic factors, so our events can be largely regarded as globalization Shock.

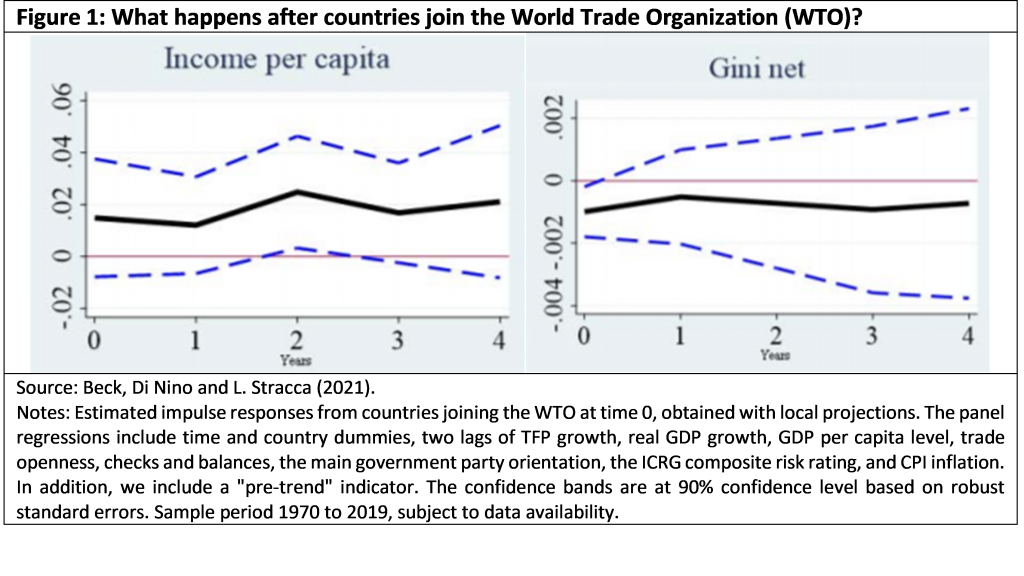

We have found that most of our “globalization shocks” will lead to a significant increase in trade openness-this is a prerequisite for treating them as global shocks in the first place. Second, according to our estimates, the impact on per capita income is mixed. Most notably, we have found little evidence that global shocks have caused more inequality.After the impact of globalization, the Gini coefficient before and after redistribution often does not change or even decline (see figure 1 Accession to the WTO).

This finding also holds when considering the alternative concept of globalization, dividing our sample into advanced economies and emerging economies, and restricting it to the post-1995 “super-globalization” era. In summary, our results show that the main impact of globalization shocks is positive and challenges the view that globalization will inevitably bring unpopular efficiency-equity trade-offs.

reference

Acemoglu, D., 2002, “Technological Change, Inequality and the Labor Market”, Economic Literature Magazine, 40(1):7-72, March.

Beck, R. Di Nino, V. and L. Stracca, 2021, “Globalization and Efficiency-Equity Balance”, European Central Bank Working Paper No. 2546.

Chinn, MD and H. Ito, 2006, “What are the important factors for financial development? Capital control, system and interaction”, Journal of Development Economics, 81(1):163-192, October.

Ebenstein, A., A. Harrison, M. McMillan, and S. Phillips, 2014, “Using current census to estimate the impact of trade and offshore outsourcing on American workers”, Economics and Statistics Review, 96(4):581-595.

Furceri D. and P. Loungani, 2015, “Capital Account Liberalization and Inequality”, IMF Working Paper, International Monetary Fund, November.

Furceri, D., P. Loungani and JD Ostry, 2019, “The aggregate and distributional effects of financial globalization: Evidence from macro and sectoral data”, Discussion Paper 14001, CEPR, September.

Goldberg, PK and N. Pavcnik, 2007, “Distributive Effects of Globalization in Developing Countries”, Economic Literature Magazine, 45(1):39-82.

Rose, AK, 2005, “Which International Organizations Promote International Trade?” International Economics Review, 13(4):682-698.

Rose, AK, 2004, “Do we really know that the WTO has increased trade?”, U.S. economy Review, 94(1):98-114.

Subramanian A. and S.-J. Wei, 2007, “WTO promotes trade, powerful but unbalanced”, Journal International Economics, 72(1):151-175.

This article is written by Roland Baker, Virginia Dinino with Livio Straka.