Now seems like a useful time to reassess some of the statements made in the wake of the tragic disaster that hit Puerto Rico in September 2017. First, the American death toll (Contrary to Mr Trump’s ostensible assertions, these are not Americans) is much higher than some reviewers claim. Second, the argument that economic policies adopted in 2016 and 2017 (ie, PROMESA-related austerity measures) caused more deaths than Hurricane Maria. In the end, the economic challenges that existed before the hurricane — including the lack of tax revenue — remain, even as the economy has rebounded.

Impact on excess mortality

First, let’s recall that some commentators believe that the death toll after a hurricane is no more than 200-400. Even after being instructed on the implications of the data, some still provide unrealistically low estimates.

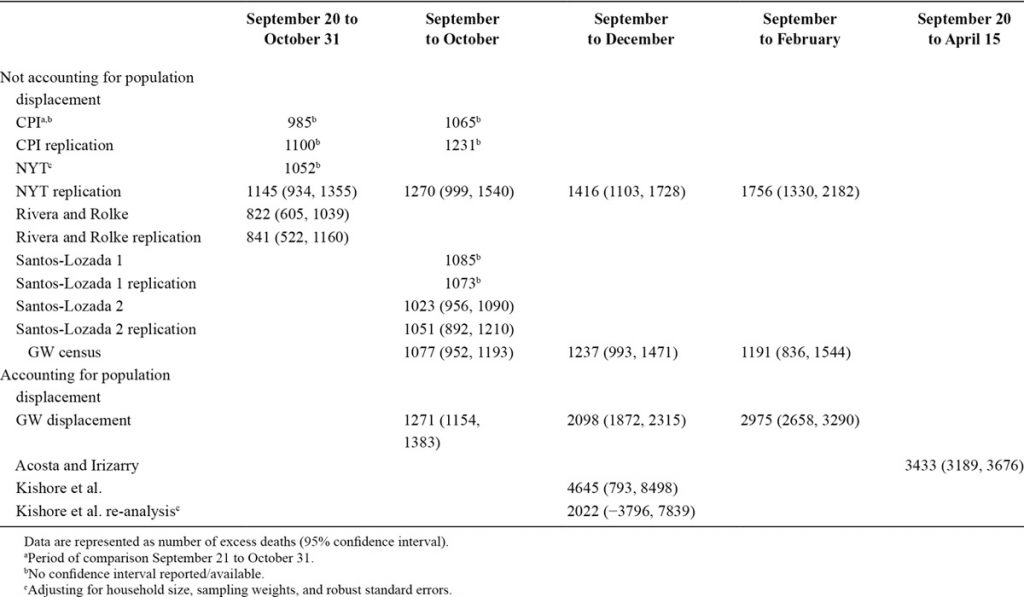

From Sandberg et al. (July 2019) in Epidemiology:

Now compare with instant reviews on Econbrowser, e.g. from Steven KopitzMay 31, 2018:

The number of PR excess deaths recorded by the Bureau of Statistics at the end of the year was only 654. Most of these occur during the last ten days of September and throughout October. While the state ownership of the public utility utility has exacerbated the outages there, most of the excess deaths are likely to happen anyway, given the terrain and the strength of the hurricane. So there could be 300-400 deaths, no matter what anyone can do to fix the power. The rest can basically be attributed to state ownership of the power company.

I will note that the excess deaths in December were cut in half. Thus, the data suggest that hurricanes accelerate the death of the sick and dying rather than kill them outright. I expect the excess deaths in a year (eg, by October 1, 2018) may total 200-400. Still a significant number, but certainly not 4,600. [emphasis added-MDC]

Latest (6/4) Analysis by Mr. Kopits To conclude, even with updated data:

Therefore, the year-end excess death toll of 1400 may be considered a definite number in practice.

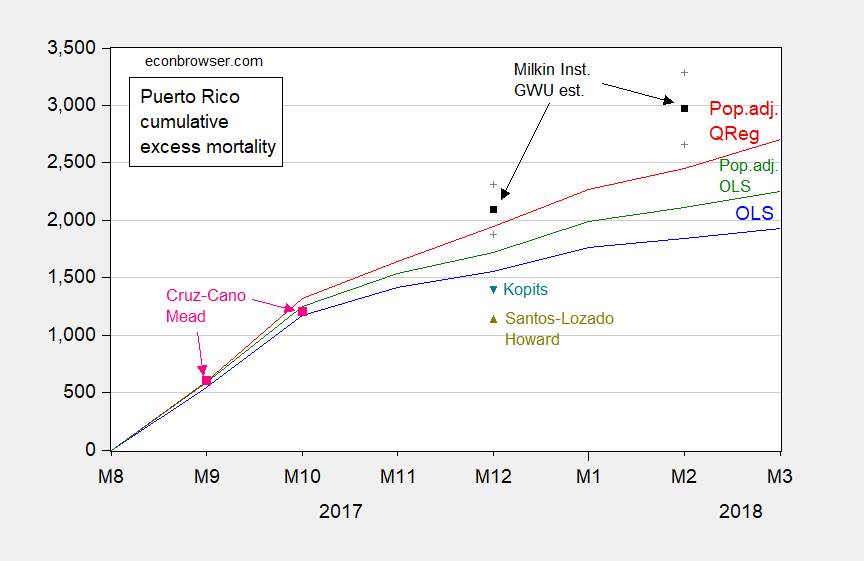

I think “firm” is the adjective to avoid in these situations.Here is a graph showing selected estimates from this Published April 2019which includes some earlier estimates.

figure 1: Cumulative excess deaths since September 2017, for simple time dummy OLS model (blue), OLS model adjusted population (green) and quantile regression model adjusted population (red), Milken Institute point estimates (black) Squares) and 95% confidence intervals (grey +), Santos-Lozada, Howard letter (yellow-green triangles), Cruz-Cano and Mead (pink squares), Kopits (cyan triangles). Not pictured above: Kopits estimate 300-400 in October 2018. Source: Author’s calculations, Milken Institute (2018), Santos-Losada and Howard (2018), Cruz Cano and Mead (2019)and Kopit (2018).

Austerity costs more than hurricanes?

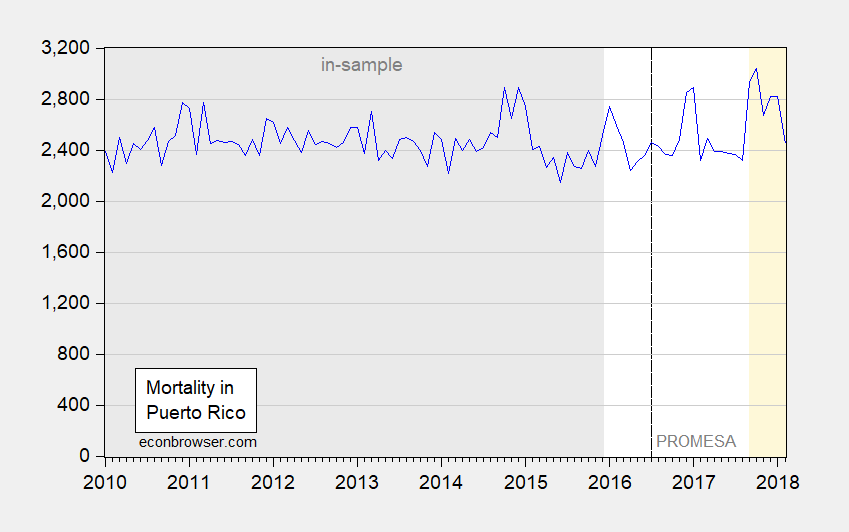

What about the argument that PROMESA-related austerity measures have resulted in higher death rates than hurricanes? [extensive argument here] . To assess this argument, first consider February 2018 mortality data.

figure 2: Monthly mortality (blue). Grey indicates in-sample period; orange shading indicates Hurricane Maria and post-hurricane period; dashed line at PROMESA legislation. resource: Santos-Losada and Howard, 2017Vital Statistics released in June.

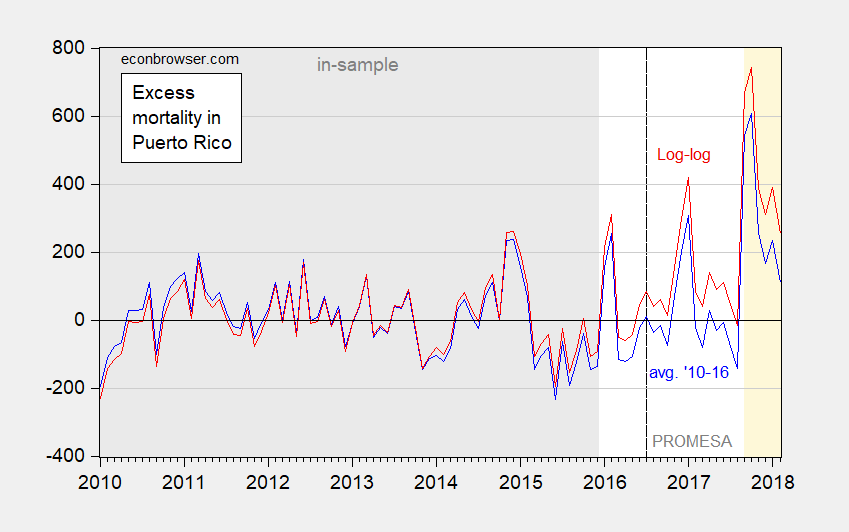

Second, now consider constructing counterfactuals before and after PROMESA implementation that excludes austerity measures (legislation passed in July 2016, controls came into effect in October 2016). I do this by estimating two equations: (1) a simple average over the period 2010-2015, and (2) a log-OLS regression norm (and a dummy for October 2014) that includes population estimates. 2016 appears to be an appropriate turning point for austerity Brad Setser’s discussion of Puerto Rico’s finances. These specifications are discussed this post. I show the implied excess mortality data in Figure 3.

image 3: Monthly excess mortality calculated using 2010-15 averages (blue), population adjusted using 2010-15 sample (red), population is a cubic interpolation of the IMF world economic outlook database data. Grey indicates in-sample period; orange shading indicates Hurricane Maria and post-hurricane period; dashed line at PROMESA legislation. resource: Santos-Losada and Howard, 2017vital statistics released in June, International Monetary Fund Wow April 2018 Databaseand the authors’ calculations.

Note that in both cases most of the pre-Maria deviations were not statistically significant at 10% msl. In other words, one cannot generally reject the null hypothesis that there is no excess mortality due to austerity, pre-Maria.

Third, it is instructive to consider the excess mortality in 2016M01-2017M08 and compare it with the excess mortality in 2017M09-2018M02. If population change in 2016-17 is assumed to be zero, the red line can be used to estimate the cumulative death toll (“average ’10-’16”), which suggests a small impact of austerity.

Figure 4: Monthly cumulative excess mortality with population-adjusted specification (blue) using IMF cubic interpolation world economic outlook Database data and using the 2010-15 average (red). Orange shading indicates Hurricane Maria and the post-hurricane period; dashed line at PROMESA legislation. resource: Santos-Losada and Howard, 2017vital statistics released in June, International Monetary Fund Wow April 2018 Databaseand the authors’ calculations.

However, a more realistic assessment relies on adjusting for population counterfactuals. This results in the blue line labeled “log-log”), which seems to validate the proposition that too many deaths start to occur before the hurricane makes landfall. Interestingly, however, neither approach directly contradicts the idea that most of the excess mortality since January 2016 is due to Hurricane Maria.

I conclude that, using statistical analysis, the inference is very fragile because the excess deaths from austerity policies before and after Maria exceeded the number of deaths after Hurricane Maria.

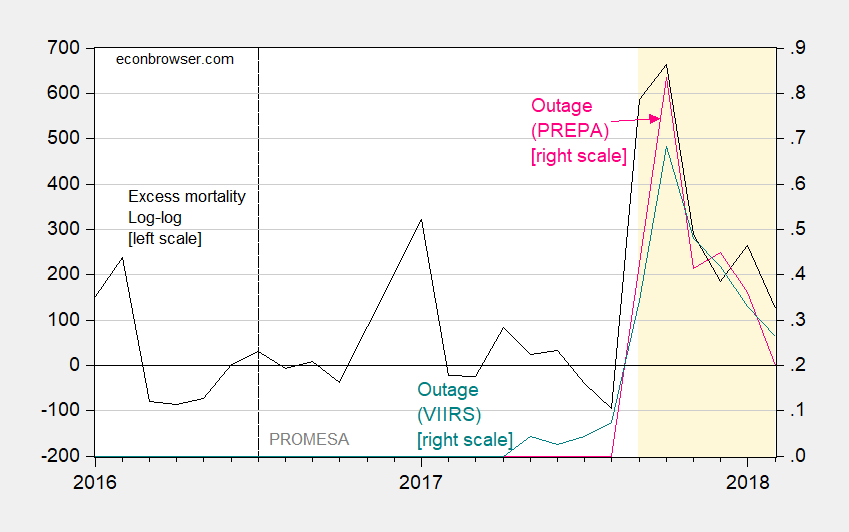

In support of this, I also found that using the reported grid outage data Shermeier (2018)excess mortality rates calculated using population adjustments closely matched outage data from PERPA (utility) or Suomi National Polar Orbit Partnership Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (NPP VIIRS).

Figure 5: Monthly excess mortality with population-adjusted specifications (black) using IMF cubic interpolation world economic outlook Database data and power outages from PREPA (pink) and VIIRS as a percentage of the total, e.g. Shermeier (2018). Orange shading indicates Hurricane Maria and post-hurricane period; dashed line at PROMESA Legislation. resource: Santos-Losada and Howard, 2017vital statistics released in June, International Monetary Fund Wow April 2018 Databasepersonal communication from Jacob Shermeyerand the authors’ calculations.

Regression for the period 2007M04-2018M02 with a blackout slope coefficient of 826 using Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) data and 950 using VIIRS data, both using HAC robust error statistically significant, adjusted R2 = 0.83 and 0.72, respectively. For example, this means 639-690 excess deaths due to the October blackout (and related factors). (Excessive mortality rates may be directly due to power outages, or due to power outage-related disruptions in communications and water service failures.)

How bad is the federal response to Puerto Maria?

Skip paper towel optics, some reports (eg, Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Homeland Security) with exact documentation FEMA underperformed. In addition, academic analyses document different responses that occurred during the same period—i.e. Greater response to hurricane landfall in Texas and Florida.

economic outlook

After a catastrophic disaster response failure, Puerto Rico’s economy recovered to pre-hurricane levels, but was sunk by the coronavirus pandemic. Figure 6 below shows the GDP and economic activity indices.

Image 6: GDP Ch2012$ in millions (blue bars, left log scale) and Economic Activity Index (EDB-EAI) sa (blue, right log scale). The NBER uses shades of grey to define the peak and trough dates of the recession. resource: Bank of East Asia, bank for economic development of puerto ricoand NBER.

The broadest measure of activity – GDP – is reported only through 2020, while the economic activity index – based on employment, electricity generation, gasoline consumption and cement sales – extends to August 2022 and measures only parts of the economy. As the graph shows, while (measured) economic activity has rebounded, it has slowed in recent months. This pattern appears in civilian employment (although not in a series that establishes a series).

Figure 7: Puerto Rico nonfarm employment (blue), private nonfarm employment (tan), civilian employment (green), all in the 000s, sa. The NBER uses shades of grey to define the peak and trough dates of the recession. resource: BLS and NBER.

Federal aid related to the pandemic is coming to an end.This fiscal drag adds to core long-term challenges for uncompetitive economies (in part because shipping and other shipping regulations) as well as huge government debt mired in restructuring (see CRS).see also 2017 Economic Analysis by Gregory Makoff and Brad Setser.

Some of these challenges are tricky, while others are relatively easy to solve.For example, abandoning Puerto Rico’s Jones Act lowers prices in some cases $1 billionwhich is significant for an economy worth about $103 billion in 2020.