Today we are fortunate to be able to present guest contributions written by the author Georgias Georgiadis (European Central Bank), Helena Lemezzo (European Central Bank), Arnold Meyer (European Central Bank), and Cedric Till (Graduate School of the Geneva Institute of International and Development). The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Central Bank or the euro system. They should not report like this.

The U.S. dollar occupies a dominant position in the international commodity and financial markets, far exceeding the economic weight of the United States. A core issue of international economics is the degree of stability of this role. Although the birth of the Euro did not replace the U.S. dollar, China’s economic rise may pose a greater challenge to the U.S. dollar, especially when Chinese policymakers are keen to enhance the renminbi’s international role rather than being more non-interfering with Europeans.

Is such a policy effective? In a recent paper (Georgiadis et al. 2021) We focus on invoices for international trade, comparing economic fundamentals and the impact of policy measures. Pricing is a relevant aspect of the international role of currencies, because the dollar’s dominance is not exclusive, and the role of the renminbi, although still small, is increasing. Specifically, 40% of international trade flows use the U.S. dollar, while only 10% of trade involves the United States as a source or destination country (Goldberg and Tille, 2008; Gopinath, 2015; Boz et al., 2020). This shows that the U.S. dollar is heavily used as a vehicle denominated currency (Gopinath et al., 2020).

Comprehensively examine the impact of economic fundamentals

A large amount of literature has studied the economic determinants of invoices. A prominent aspect is the existence of strategic complementarity, which leads exporters to limit the price fluctuations of their products relative to competitors (for example, Mukhin, 2021). In the context of price stickiness, exchange rate changes play an important role in driving relative prices, and exporters have the incentive to issue invoices in the same currency as their competitors. As domestic companies account for a considerable share of the competition faced by exporters, we expect that trade flows to the United States and the Eurozone are more likely to be denominated in U.S. dollars and Euros, respectively. In addition, the need to limit relative price changes is more important in sectors where commodities are more homogeneous.

The rise of global value chains (GVC) can also play a role, because the goods sold by companies that are part of such chains include a significant portion of imported inputs, and the share of domestic value added is correspondingly low. This encourages invoicing of exports in the same currency as imports, in order to hedge costs naturally.

We use a wide range of samples to empirically evaluate the role of economic fundamentals, including currency pricing information based on Boz et al. (2020). The data covers 115 countries after 1999, showing the proportion of the U.S. dollar, euro, and national currency in each country’s imports and exports. However, this extensive sample of data does not systematically contain information about the renminbi.

Panel analysis confirmed the role of fundamentals. Exporters in the U.S. or the Eurozone use more dollars and euros respectively. A similar pattern has been observed in exports to countries linked to the US dollar or the euro. A more homogeneous commodity trade uses more U.S. dollars at the expense of Euros. Participation in the global value chain has no significant impact, but it promotes the use of the euro in export invoices, but only in the euro area countries.

The role of the renminbi is growing

Although the euro has long been regarded as the only potential challenger to the US dollar, the rise in China’s economic weight opens up the possibility of the renminbi becoming another challenger. We use a small sample of countries (not including China itself) to evaluate this. In addition to the U.S. dollar and the euro, we also have information about the use of the renminbi.

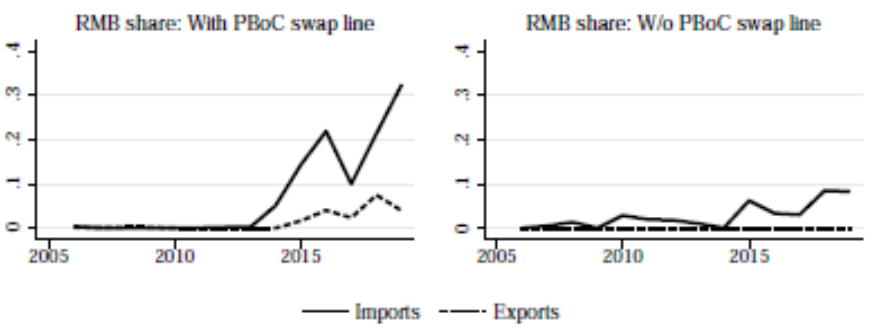

The use of the renminbi is still quite limited, but it is growing. The left panel of Figure 1 shows the number of countries where RMB denominated data is available. The graph on the right depicts the share of trade denominated in RMB in countries that use RMB to some extent, including the median (thick line) and 75day Percentile (thin line). We clearly see that the renminbi is not yet an important competitor to other currencies and is only used for a small part of trade. Nonetheless, there are still some outliers that account for a larger share of RMB pricing, and this trend is clearly positive.

Figure 1: The evolution of RMB invoices

source: Georgiadis et al. (2021). notes: The chart on the left shows the number of countries with RMB denominated data. The graph on the right shows the share of imports and exports denominated in RMB, the median (thick line) and 75day Percentile (thin line).

Our analysis shows that the role of the rising renminbi partly reflects the same economic fundamentals considered by the euro and the dollar, albeit in very different ways. In general, the increase in trade with China is related to the greater use of US dollars at the expense of the euro. Focusing on a specific area shows a pattern of differentiation. Among European countries, a higher share of imports from China leads to more use of the euro at the expense of the dollar. In contrast, countries in Southeast Asia and Oceania use the U.S. dollar more at the expense of the Euro when conducting more trade with China. However, with the exception of the trade between Oceanian countries and China, there is basically no impact on the use of the renminbi.

Active policy

Although European officials did not believe that the euro’s international role is primarily driven by market forces until recently, Chinese counterparts have played a more active role. Specifically, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has established currency swap lines with the central banks of other countries to facilitate RMB payments and promote its use in international trade. Bahaj and Reis (2020) show that the policy of establishing swap lines to reduce financial transaction costs can theoretically lead to more use of corresponding currencies in international trade invoices.

We did record that the swap line is related to the greater use of RMB in international trade invoices. Figure 2 shows the share of RMB in import and export invoices, comparing countries that established swap lines with the People’s Bank of China at some point (left) and those that did not (right). We clearly observe that the RMB usage rate of the former group is higher.

Figure 2: RMB denominated and currency swap lines

source: Georgiadis et al. (2021). notes: The graph shows the median RMB-denominated shares of countries that have established swap lines with the People’s Bank of China (left) and those that have not established swap lines with the People’s Bank of China (right).

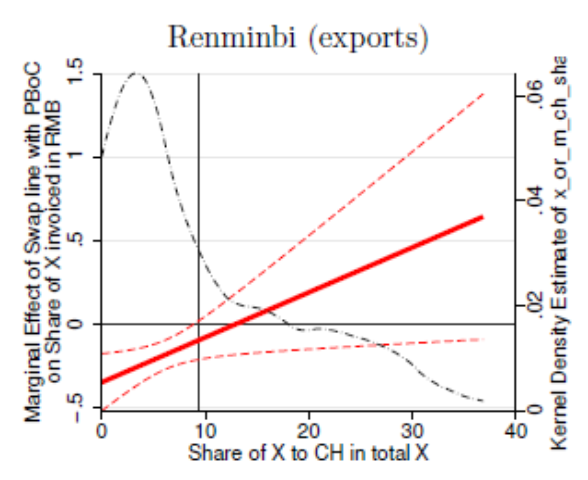

Looking at the data more closely, we found that only in a country where China is a fairly large trading partner, the swap line is related to the greater use of the renminbi. Figure 3 shows the impact on the swap line denominated in RMB based on the share of exports into China (the import pattern is similar). Although establishing a swap line with a country that does not have a large trade volume with China will slightly reduce the use of the renminbi, for those countries with a high export share to China, the impact will become less negative, but change. Be positive.

Figure 3: The impact of swap lines on RMB invoices

source: Georgiadis et al. (2021). notes: This graph shows the marginal impact of the People’s Bank of China swap line on the renminbi denominated value, which depends on a country’s share of exports to China. The solid line represents the point estimate, and the dashed line represents the 90% confidence interval. The blue dotted line is the nuclear density estimate of China’s export share distribution.

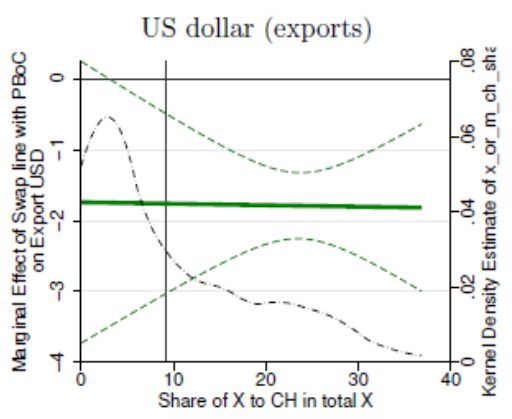

The additional use of RMB is reflected in the share of which competitor’s currency? Figure 4 shows the effect on U.S. dollar (left) and Euro (right) invoices, and its structure is the same as Figure 3. Higher renminbi use comes at the expense of the U.S. dollar. Regardless of the degree of impact on the U.S. dollar, its impact is negative. A country trades with China. Euro invoices have also been reduced, but only in countries that do a lot of trade with China. In addition, the impact on the euro is still far less than the impact on the dollar.

Figure 4: The impact of swap lines on the pricing of US dollars and Euros

source: Georgiadis et al. (2021). notes: This graph shows the marginal impact of the People’s Bank of China’s swap line on USD-denominated (left) and Euro-denominated (right), depending on a country’s share of exports to China. The solid line represents the point estimate, and the dashed line represents the 90% confidence interval. The blue dotted line is the nuclear density estimate of China’s export share distribution.

The rising role of the renminbi’s pricing reflects economic fundamentals, albeit only on a regional basis, and the People’s Bank of China’s policy of establishing swap lines to promote the use of its currency. Our analysis shows that the specific currency used to reduce the use depends on the invoice drivers considered. Economic fundamentals indicate that China’s integration into world trade benefits the U.S. dollar and the renminbi (to a certain extent) at the expense of the euro, thereby strengthening the dominance of the U.S. dollar. In sharp contrast, the establishment of swap lines has increased the use of the renminbi at the expense of the U.S. dollar, and the impact on the euro has been much milder.

Therefore, our analysis shows that the rise in the role of the new challenger currency does not necessarily come at the expense of existing challengers, but it can be at the expense of the dominant currency. The exact model depends on the specific factors that support the rise of the new currency’s status.

refer to

Bahaj, S. and Reis, R. 2020. Launch international currencies. CEPR Discussion Paper 14793

Boz, E., Casas, C., Georgiadis, G., Gopinath, G., Le Mezo, H., Mehl, A., Nguyen, T., 2020. Currency pricing model in global trade. sound, October 9th.

Georgios G., Le Mezo, H., Mehl, A., Tille, C., 2021. Fundamentals and policies: Can the dominance of the US dollar in global trade be weakened? CEPR Discussion Paper 16303. [ungated version, GIIDS working paper]

Gopinath, G., 2015. International price system. NBER working paper 21646.

Gopinath, G., Boz, E., Casas, C., Diez, FJ, Gourinchas, PO, Plagborg-Møller, M., 2020. The dominant currency paradigm. American Economic Review 110, 677-719.

Goldberg, L., Tille, C., 2008. The use of vehicle currency in international trade. International Journal of Economics 76, 177-192.

Mukhin, D., 2021. The equilibrium model of the international price system. Mimi.

This article is written by Georgias Georgiadis, Helena Lemezzo , Arnold Meyer, with Cedric Till.